History Of Color Science

Predicting Biology from Behavior

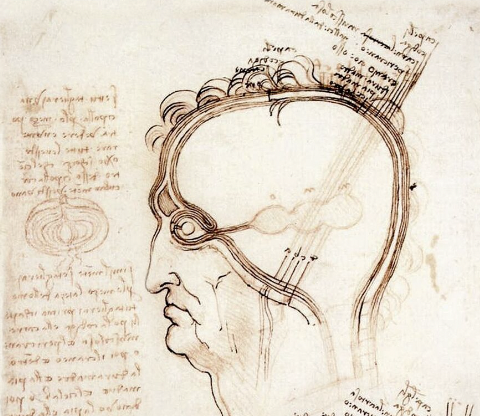

In Ted Chiang's Exhalation, a mechanical being notices that their species' perception of time has sped up and suspects that this is because their brains have gotten slower. They then build an intricate device that lets them peer inside their own brain and observe the machinery that gives rise to their thoughts: a complex engine at the center of which was a latticework of wires with gold leaves held in various positions based on an ever-changing pattern of air flow. They deduce that 'All that we are is a pattern of air flow'. The slowing down of their brains was due to an increase in the air pressure of their surroundings. Following that line of thinking, they arrive at the conclusion that eventually the difference in air pressure between their brains and surroundings will be equalized. When that happens, their thoughts will cease altogether.

I love the image that Exhalation conjures of a person observing their own brain in action. But something else that struck me about this story was how their initial hunch came not from looking inside the brain, but by observing their own behavior and their environment. Centuries before we invented fMRI machines, stuck electrodes inside the brains, or engineered proteins to make the brain glow, scientists made unreasonably accurate predictions about how our brains work. They did this by making careful observations of the world around us, introspecting on their own experiences and behavior, and through rigorous reasoning. This post is about one example of the boldness of predicting biology from behavior: the science of color vision.

We know that most humans are 'trichromats'. Our eyes have three color receptors that are sensitive to different wavelengths of light and this gives rise to our ability to perceive color. But how exactly did scientists figure this out?

Studying the stimulus: What is light?

All physicists are simply future neuroscientists. Newton was no different.

To understand how looking at light gives rise to the perception of color, we need to first understand what light is. Newton did a series of elegant experiments to understand the fundamental components of light.

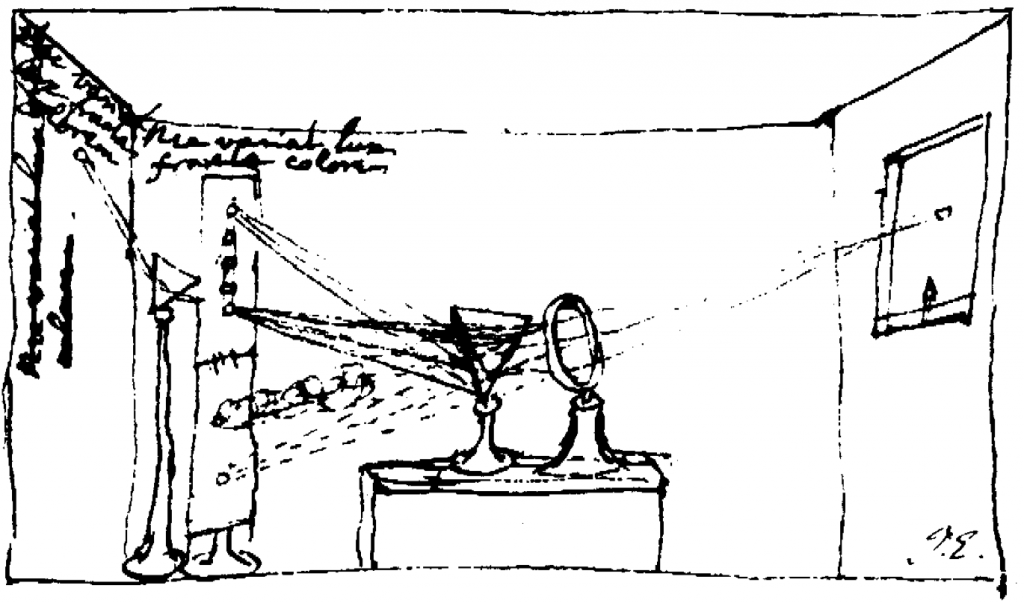

He let sunlight in through a tiny hole in his dark room. He placed a prism in the path of the light and let the refracted light fall upon the screen. Light passed through the prism and formed a rainbow on his screen. He noted that different rays of light differ in how they were refracted, and that the degree of their refractiveness corresponded to the color in which they appeared.

Side note: If you're curious about exactly why this happens, I recommend checking out this video by 3blue1brown.

Then, Newton cut a slit on the screen to allow only a portion of the rainbow to pass through. He placed a second prism in the path of this ray. He observed that:

Newton's prism had split light into its fundamental components. He then used lenses to converge the rays that passed through the first prism. He observed that he could get back the original light, suggesting that the decomposition of light was reversible.

But the part that Newton had not considered was the relationship between the wavelength of the ray of light and what it means for it to appear a certain color to humans.

Studying behavior: Metamers

Color is in the eye of the beholder. Or, more accurately, in the brain of the beholder. This insight was crucial in uncovering the biological basis for color vision. It shifted the emphasis from looking outwards, only studying light itself, to looking inwards and studying the system that is doing the actual perceiving. It might seem obvious, but most things that are obvious in hindsight were nothing but when they were first discovered!

People have spent a long time wondering about what it means to experience color and whether my blue is the same as your blue. Newton and others had helped provide an understanding of the basics of how light worked, but for a long time, we still lacked the tools to study the physiology of the eye. How then to get any insight about what gives rise to the perception of color?

Newton's work showed us that sunlight is made up of spectral components of different wavelengths. Early theories suggested that the eye contained 'retinal elements' that vibrated in response to light stimulation, and these vibrations helped us see. But if light was made of infinitely many rays of different wavelengths, were there infinitely many retinal elements that each respond to a given wavelength?

Thomas Young, amongst other 'future neuroscientists' including Helmholtz, Maxwell, and Grassman, was one of the first to propose that there were only three distinct receptor types in the retina. The basis of their assertion was a set of neat behavioral results in what we now call 'color-matching' experiments.

They presented a person of normal color vision with a 'test' light made up of some arbitrary spectral composition. Then, they asked the person to 'match' the appearance of the test color by adjusting the intensity of a set of lights with fixed spectral distributions - called primarily lights.

They found that having two primary lights was insufficient to match all colors, while having four was too many. These behavioral experiments proved that it was necessary and sufficient to have three appropriately chosen primary lights to match the appearance of any light of arbitrary spectral composition. This meant that there were infinitely many lights with different spectral distributions that all appeared identical to humans.

To illustrate this, look outside your window at the sunlight. Okay, now look at this photo of the sky:

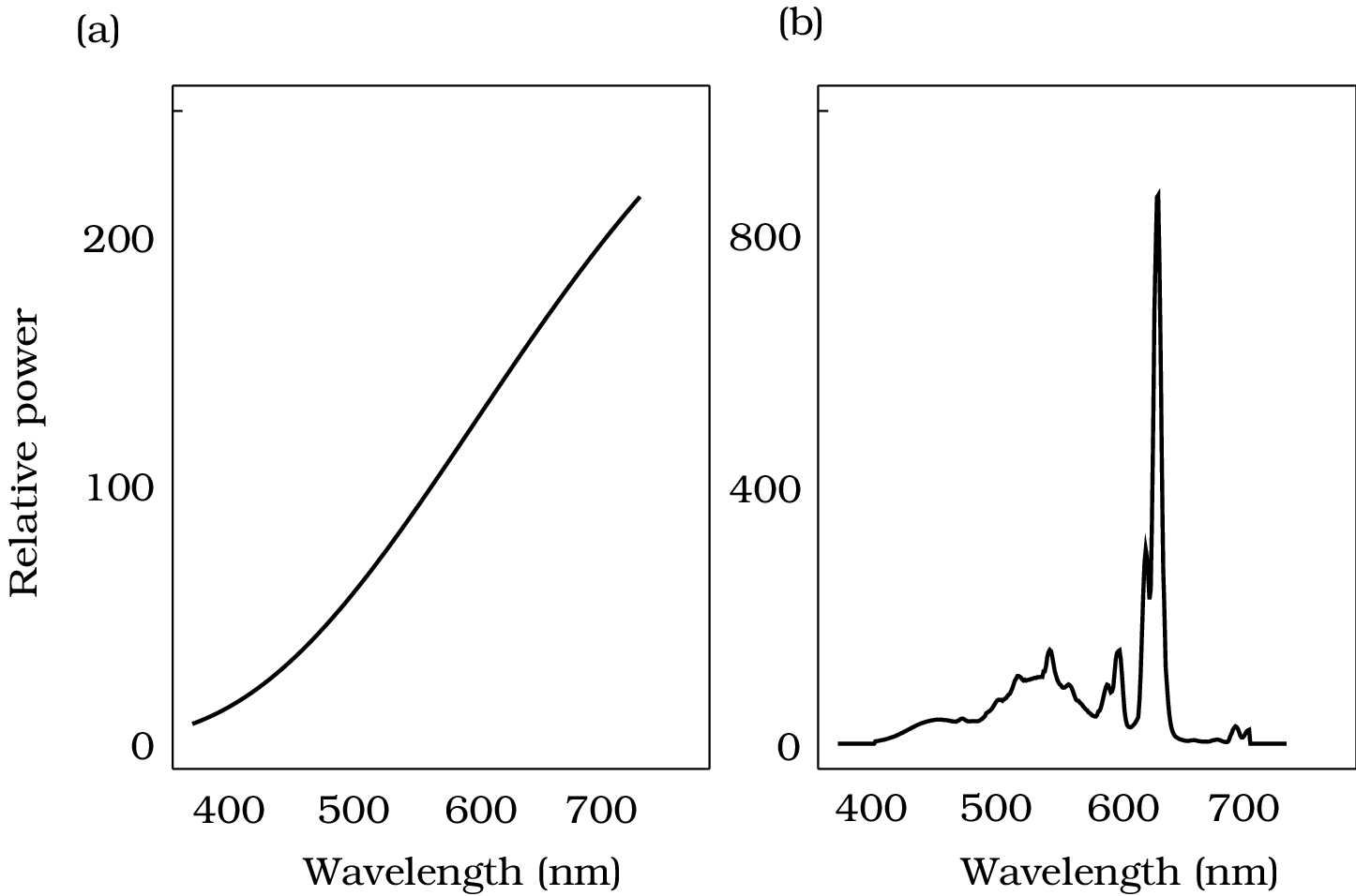

In these two cases, your eyes were stimulated by light with very different spectral power distributions. Below, the left panel shows an approximation of the spectral power of the sun. On the right is the spectral distribution of the light coming out of a typical computer monitor which has been calibrated to produce an image that is identical to sunlight to most human observers. Such stimuli, that are physically different but perceptually indistinguishable, are called Metamers.

From foundations of vision, chapter 4

Disclaimer: The color-matching demo above is misleading. We cannot perform a true trichromatic color matching experiment on a computer monitor. The reason for that is evidence of the enormous impact that this behavioral finding has had on the larger world: most displays are built with only three different types of phosphors that emit light of particular spectral distributions. By adjusting the relative intensity of the three lights, we can produce the percept of any color. But a picture of sunlight on a display monitor is only a metamer of the sunlight we see outside our window. The science of human color perception made the engineering of these devices possible. (And the International Commission on Illumination codified these standards in 1931, years before we actually measured cells in the eye!)

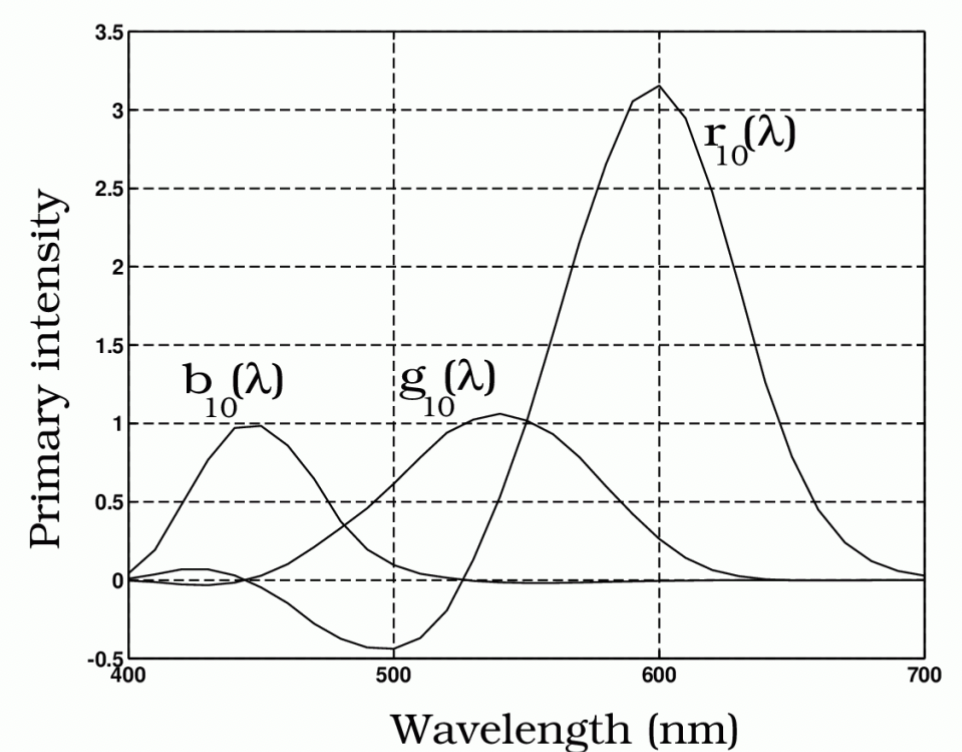

The scientists of the 1800s didn't just stop at identifying the number of distinct primary lights required to match human vision, but also made precise predictions of 'color-matching functions': the intensity of each chosen primary light needed to match a monochromatic light of a given wavelength. For example, to get a monochromatic light of wavelength 550nm, what we need is an intensity of 1 for R, intensity of 1 for G, and intensity of 0 for B.

The color matching functions are not unique: So if we used two distinct sets of primary lights, we will arrive at different color-matching functions. But the two functions are related by a linear transformation. We can think of this linear transformation as adjusting the intensities of the first set of primary lights to match the intensities of the second set of primary lights.

Based on these findings, they predicted that the human eye must contain three types of receptors. Moreover, they predicted that the absorption spectra of these three receptors must explain the color-matching results, i.e. they will be related to the color-matching functions by a linear transformation.

This was all figured out by the 1850s. It took us more than a hundred years after that to actually test and verify these predictions by studying the properties of photoreceptors in the human eye!

Studying Physiology: Cones

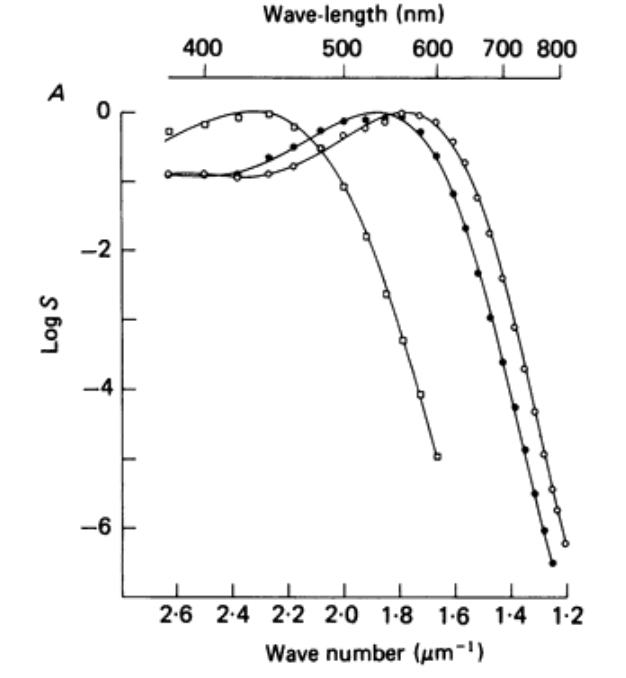

To conclude the saga and discover the biological basis of human trichromatic vision, in the late 1900s, Baylor, Nunn, and Schnapf painstakingly measured the spectral sensitivities of the different cone types. To do this, they harvested retinas, the sheet of tissue at the back of the eye where light falls. Our retina contains primarily two types of photo-receptors: Rods and Cones. When light falls on these cells, they convert this to electrical signals. Rods operate more in 'scotopic' vision, that is when it is relatively dark. Cones operate in photopic vision, when it is bright, and mediate 'color vision' because there are three types of cones that are sensitive to different wavelengths. The fact that there are three types of cones, was known by the 1980s. But their exact spectral sensitivities, that is the shape and amplitude of how much each wavelength of light excites a given cone, had not been measured. These measurements are key in testing whether the cone spectral sensitivites can explain the behavioral results from the color-matching experiments.

So, Baylor and colleagues undertook this heroic experiment. They took the harvested retinal tissue, isolated a single cone, and preserved it in a solution that keeps it alive for a few hours post-harvesting. Then, they passed monochromatic lights of various wavelengths and observed the sensitivity of different cones. They found three different cone types with spectral response functions that showed peaks in different wavelengths, which they called the short, medium, and long wavelength cones. Further, they showed that there is a linear transformation that converts the cone photocurrent measurements into the color-matching functions predicted from the behavioral experiments. This paper finally provided the biological basis to explain the results from the color-matching experiments.

I first learned about this from Eero Simoncelli when I attended the CSHL course on vision. Here's a quote from a talk of his where he does a much better job of conveying the essence of this scientific story and why it's worthy of praise. (In his own career, he sought to and succeeded in discovering a similar scientific story: Metamers and pattern vision )

Studying others: Predicting Behavior from Biology

So far, we've talked about a story of the triumph of behavioral science in predicting biology. But often, scientific progress comes from an Inside-Out approach - studying biology to predict psychology. I'll write about one such case that I first came across in Ed Yong's book 'An Immense World'.

Once scientists established that normal human vision is trichromatic and that the biological basis for this is the three types of cones we have, they started to look for situations where this was not the case. Color-blindness is one obvious example that people were aware of for centuries (Maxwell, one of the protagonists of the color-matching experiments, wrote extensively about its implication for color-blindness). But what of those that can see more than I can?

Gabriele Jordan and colleagues are interested in whether there may be tetrachromats hiding amongst us - humans with four distinct cones who are able to perceive colors that are identical to most of us trichromats. But searching for tetrachromacy is not easy for a variety of reasons. For one, they might not even realize their perception is different!

Instead of hoping that the tetrachromats will self-identify and call up their nearest color researcher, these scientists put together a set of conditions to narrow the search down. The key to figuring out the right set of conditions lies in understanding the genetics behind cone cells.

First, it's far more likely that a female is tetrachromatic compared to a male. It is also more likely that a male has color-vision deficits compared to a female. This is because the genes that determine the properties of your cones is in your X chromosome. So it's possible for females to inherit both an X-chromosome with the typical S, M, L cone genes and the other X-chromosome with a wonky copy of, say, the M-cone gene such that this cone responds to a slightly different wavelength compared to typical human M-cones. But how to narrow down which females to study to find tetrachromacy? The key is to look at the mothers/daughters of males who exhibit a specific type of color deficiency called "anamalous trichromacy" that is easier to spot behaviorally . An anamalous trichromat has an M or L cone with slightly shifted wavelength preferences. The mother/daughter of an anamalous trichromat is an 'obligate carrier' of this spectrally shifted hybrid cone, in addition to having the standard S, M, and L cones.

So these researchers put out TV ads to recruit boys who are anamlous trichromats and their mothers to participate in their study. Having these four cones is a necessary but not sufficient condition for exhibiting behavioral tetrachromacy. A few more conditions need to be met: the extra cone needs to be responsive to a very specific wavelength, it has to be abundant in the part of the retina that perceives information in the fovea, i.e. the central portion of our visual field, and perhaps the most complicated requirement, the brain needs to be able to process its responses to actually use the information the fourth cone relays to give rise to perception.

The researchers narrowed down their list to twenty four eligible mothers and had them do a behavioral experiment called the Rayleigh Discrimination Test.

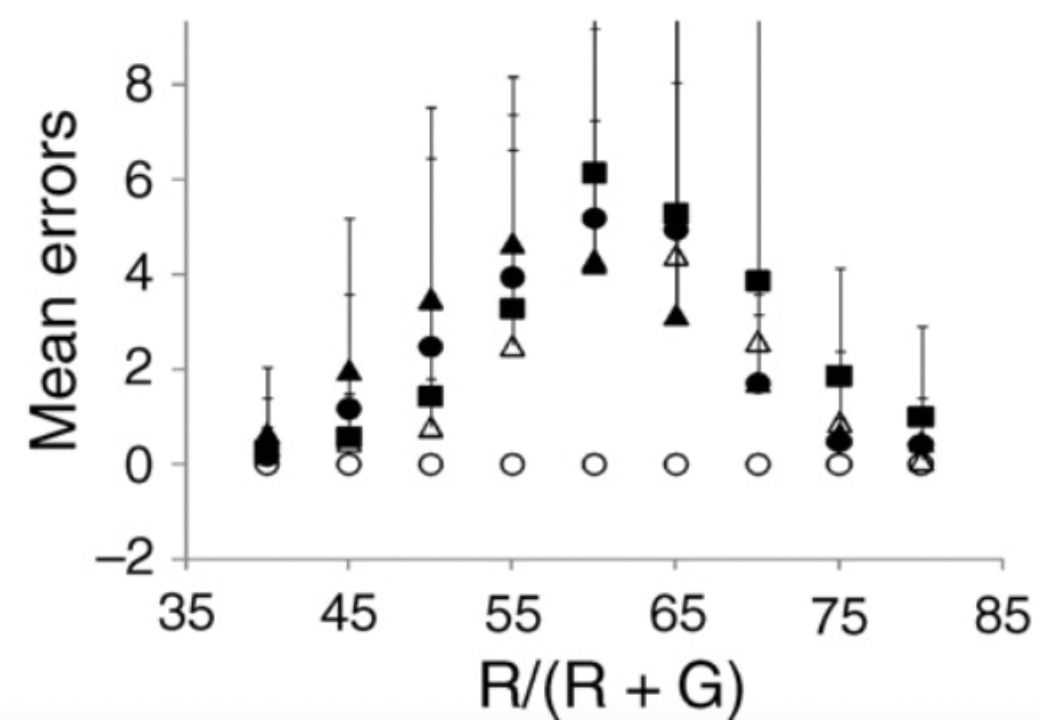

They presented three colored circles in quick succession. Two of the three circles were made of monochromatic light of wavelength 590nm. The other circle was a mixture of two lights: Red (670nm) and Green (546nm). The order of presentation of the three circles is randomized each time and the participant must guess which of the three was the mixture circle. For participants with normal trichromatic vision, for certain ratios of R and G, the mixture circle will appear to be identical to the monochromatic circle. This is the essence of the color-matching behavioral experiments we previously spoke about. However, if a person has a fourth cone that had a preferred wavelength of XX and they were able to use the signals from that cone for perception, they might be able to tell apart colors that are identical to others.

Here's a demo to give a sense of what the experiment was like. Disclaimer: just like in the color-matching demo, this is NOT the actual test. We can't perform the test for tetrachromacy using normal display monitors because they only have three types of phosphors.

In this Journal of Vision paper from 2010, Jordan and colleagues found that only one of the twenty four obligate carriers they studied was actually able to discriminate between lights that are totally identical to trichromats. Below is a plot of the mean errors in the Rayleigh Discrimination task as a function of mixture ratio. Error rates increased for intermediate ratios for most participants. But see the open circles -- subject cDa29 -- they had no trouble doing this task which stumped the rest of them.

In this case, the knowledge of biology, that the properties of our cones constrain our perception and that a subset of females who are mothers of anamalous trichromats might have four cones tuned to specific wavelengths, informed who to study and what to look for in the behavior. So we've come full circle, from behavior predicting biology to biology predicting behavior.

Most of what I wrote about here has been previously explained by others. In particular, I recommend checking out:

- Foundations of vision by Brian Wandell (chapter 4)

- Ed Yong's An Immense World (chapter on color: "Yurple, Rurple, Gurple")

- Eero Simoncelli's lecture on probing sensory representations

Thanks to Rithika Sankar for patiently explaining basic genetics to me.

Please let me know if you spot any errors or mistakes. I'd like to be as accurate as possible, so I greatly appreciate any feedback.